Ephemeral Metal: The Art of Oxidation and the Patina of Time on Antique Sewing Feet

There’s a particular beauty that time imparts, a richness and depth that can’t be replicated. We see it in crumbling architecture, in faded photographs, and profoundly, in the metal components of antique sewing machines. Especially captivating are the sewing machine feet – often overlooked, but telling silent stories of decades of use, of countless garments stitched, and the enduring testament to a forgotten era of craftsmanship. These aren’t just pieces of metal; they are ephemera, whispering tales of a world where things were made to last, and the marks of that longevity are both a record and a reward.

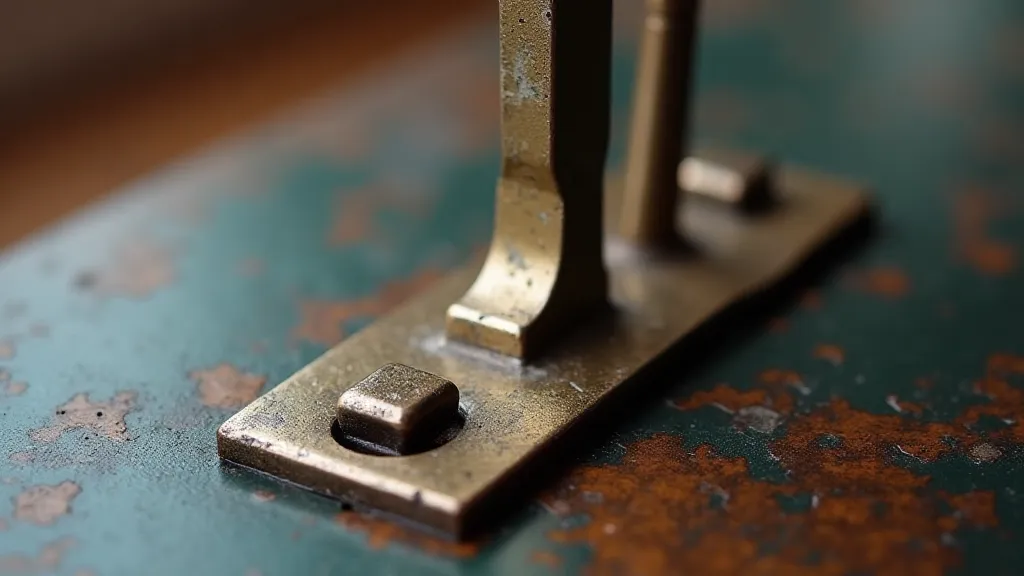

My own fascination began years ago, rummaging through a dusty estate sale. Surrounded by chipped china and faded textiles, a box of sewing machine attachments caught my eye. Among them were a dozen or so feet, each subtly different, each bearing the unmistakable character of age. They weren't pristine; they weren't “new.” They were lived. The dark, mottled surfaces, the slight pitting, the way the light caught the uneven textures – it was instantly mesmerizing. I wasn't just acquiring tools; I was acquiring history.

The Chemistry of Change: Understanding Oxidation

The visual narrative we see on these antique sewing machine feet is largely a consequence of oxidation, the chemical process by which metal reacts with oxygen. Iron, in particular, readily oxidizes, forming iron oxide—what we commonly know as rust. However, the appearance isn't always straightforward rust. Depending on the alloy composition (often a mix of iron, steel, and other metals), the presence of moisture, and the surrounding environment, various other metal oxides and compounds can form, creating a wide spectrum of colors and textures. A foot might display patches of deep bronze, hints of green (copper compounds), or a matte black sheen. The beauty lies in the complexity and unpredictability of it all.

Different manufacturing processes also contribute to the final appearance. Early steel production wasn't as refined as it is today, resulting in higher levels of impurities. These impurities become active participants in the oxidation process, influencing the colors and patterns that develop over time. The original surface finish, too, plays a critical role. A rougher, less polished surface provides more area for oxidation to occur, leading to a more intricate patina.

Beyond Rust: The Aesthetics of the Patina

While rust is a form of oxidation, what we often admire on antique sewing machine feet is more accurately described as a “patina.” A patina is a surface film that develops naturally on metal, protecting it from further corrosion while simultaneously enhancing its appearance. It’s a sign of maturity, a badge of honor earned through years of exposure and use. To dismiss it as simply “rust” is to miss the nuance and the story it tells.

The color palette achievable on these feet is remarkable. The subtle shifts in color—from warm browns and oranges to deep greens and blues—speak to the environment in which they existed. A foot stored in a damp basement will display a different patina than one that spent decades in a dry attic. The beauty isn's solely about the color itself, but about the way these colors blend and interact, creating a surface that is far more compelling than any factory finish could ever be. There’s an undeniable organic quality to it, like looking at a miniature landscape sculpted from metal.

Different Feet, Different Stories: A Brief Overview

The type of foot itself influences the nature of its patina. Edge stitching feet, frequently used in close quarters, often bear more concentrated wear patterns. Gathering feet, with their more complex shapes, tend to accumulate more grime and develop thicker layers of oxidation in crevices. Buttonhole feet, subjected to repeated stress and friction, may show distinct polishing or smoothing alongside the patina.

Early Singer feet, particularly those from the late 1800s and early 1900s, are frequently found with a characteristic mottled bronze and brown patina. Later feet, especially those from the mid-20th century, often display a darker, more uniformly black appearance due to changes in manufacturing processes and the alloys used. Examining a collection can be a fascinating study in metallurgy and industrial history.

Preservation and Appreciation: A Delicate Balance

The question of preservation is a complex one. Do we strive to remove the patina, revealing the original factory finish? Or do we embrace it as an integral part of the foot’s history? There's no single right answer. Many collectors prefer to preserve the patina "as is," recognizing its historical significance and its aesthetic appeal. Cleaning too aggressively can damage the surface and remove valuable information about the foot's past. Gentle cleaning with a soft cloth and mild soap is often sufficient.

However, in cases of severe corrosion that threatens the structural integrity of the foot, more intervention might be warranted. Careful electrolysis or chemical reduction can be used to remove heavy rust, but it's a process that should be undertaken by someone with experience and a thorough understanding of metalworking techniques. The goal should always be to stabilize the foot and prevent further deterioration, while respecting its original character.

The Enduring Legacy

Antique sewing machine feet are more than just tools; they are tangible links to a bygone era. They represent a time when craftsmanship was valued, when things were built to last, and when the marks of time were embraced as a testament to durability and character. By understanding the chemistry of oxidation, appreciating the aesthetics of the patina, and respecting the history embedded within these small pieces of metal, we can keep their stories alive for generations to come. The ephemeral beauty of these aging metals is a constant reminder that true value lies not in perfection, but in the beauty of a life well-lived – a life stitched together, one seam at a time.